Continued from Uprooting Civilization (Part 1)

“There were too many of us, we had access to too much money, too much equipment, and little by little we went insane”

Francis Ford Coppola

The Non-Evolutionary Perspective

We now know, perhaps with some relief, that evolution was not a key factor in creating a form of humanity that is now dominated by industrial civilization. To that argument I would add the critical caveat that because civilization is the primary reason for population growth and, as much as the great organs of the industrial world would like us to think otherwise, it is only this huge population – skewed in favour of civilization – that gives the impression of humanity being a civilized animal. Much like the USA claiming that Hawaiʻi is American because it is full of Americans.

But there’s little doubt that civilization is a significant, if recent, part of human history. It is also true that civilizations of many different varieties, sizes and timescales, have cropped up, apparently spontaneously across the world. This gives the impression that, if not a natural attribute of humanity, the “need” to be civilized is strongly built into the cultural make-up of a great number of humans. If one were to take the pragmatic approach then you could say that humanity is civilized, at least in terms of numbers and dominance. That doesn’t mean it is a good thing; it’s just a fact. Why this has happened in the absence of an evolutionary drive is an obvious question, and one that is very closely linked to how this happened in practical terms.

The “how?” part of the question is essentially a matter of brute power, the harnessing of nascent hierarchies and the exploitation of human vulnerabilities to benefit a burgeoning elite. I am not going to get into a discussion about the history of global civilizations, nor the impact of them on humanity and the wider environment – A Short History of Progress, by Ronald Wright is an excellent primer if you want to know more. What I will attempt is an explanation of why civilization happened in the first place, the spark that lit the fire that has now engulfed the Earth.

Origins of Civilization: Practical

It’s important to get this one out of the way first. The reason I want to address practical origins is because they are often seen as the primary reason for civilization’s birth, without actually addressing the root causes. In a way these “origins” are merely a link between the deeper reasons for humans becoming civilized, and the practical outcomes, such as agriculture, deforestation, large settlements, war, slavery and imperialism. But there is a key “why?” and that, I believe, takes its cue from the end of the last glacial period, approximately 12,000 years ago. For around 100,000 years prior to the recent retreat of northern hemisphere glaciation, there existed a state commonly known as the Ice Age. Paleoclimate analysis vividly shows the changes that took place in the heartlands of civilization, such as the Near East and southern China as the glaciers retreated. From mainly desert conditions, there rapidly developed significant areas of lush forest and others with a relatively temperate climate, peaking between 10,000-9,000 years before the present day. Under such conditions of biological plenty, formally nomadic people had less of a need to move in search of water, in-situ vegetation and, perhaps critically, building and fire-making materials. Humans are social creatures; they are also opportunistic. Under such conditions staying still for a while made perfect sense.

But that does not explain the rise of civilization.

We know from Part One of this essay that there is no natural urge to accumulate surplus, form hierarchies or allow oneself to exploit the land to its limits; the urge would have been to move on as a collective band of humans once things became leaner, but they didn’t become leaner, at least for those in power, because, agriculture rapidly took hold, storage became a basic task and a few people found they were able to dominate many. From this came imperialism, or at least widespread trade, and so it goes…

Despite the obvious conjunction between newly greening lands and a roaming population, or at a least a population that only stayed in loose settlements as with many current indigenous people, civilizations only sprung up in a few specific areas. From these they were able to spread, and the ideas of civilization started to dominate wherever they touched. This would indicate a natural pattern of human cultural development if it wasn’t for the fact that non-civilized populations still exist in relatively resource plentiful conditions all over the world. It seems, then, that civilization – or the urge to become civilized – bears more resemblance to a disease, such as cancer, than a gene.

Could it be that although eventually conditioned to become civilized, the initial urge to move towards this state was the result of a flaw in a few humans that found an opportunity?

Origins of Civilization: Psychological

Humans are, like many other mammals, communal animals that innately protect the collective above the individual. This is demonstrated by the presence of banishment in tribal peoples as the most severe form of punishment for a transgression against the tribal body, and the absence of selfishness or pride in ancient tribes. Contrary to what writers such as Jared Diamond1 continually suggest, growth in population or resource hardship – while causing stress – does not cause major conflict in uncivilized, settled, human groups; instead, in the absence of other limiting factors, it leads to migration, or alternatively the splitting off of a group from the main tribe, much as bees swarm when a hive becomes overcrowded. This resistance to conflict and the development of a larger, more hierarchical population, has its roots in natural human connections. Extensive anthropological study2 has shown that the optimum size for thriving human groups is between 100 and 300, beyond which dependency connections become weaker and splitting off becomes almost inevitable. The corollary of this is that even though humans are more than capable of living in large populations, they will not be connected to each other in the same way than if they were living in smaller groups. Where populations cannot easily disperse, hierarchies will inevitably develop which, like disconnection, is anathema to evolutionary behaviour.

The fact that hierarchies have developed, contrary to natural human behaviour, indicates something acting against our evolved need to be connected and communal. And this is where the “fatal flaw” comes in. I don’t believe for a moment that there was some spontaneous, innate urge to resist natural human behaviour; instead we have a situation that seems to relate to psychopathy – the mental state in which humans lose the need to relate to others, instead being solely driven by their own, often material, self-interest. Psychopathy has repeatedly been shown to go hand in hand with a high level of persuasiveness and authority, possibly enough to change the dynamic of a group from equitable to authoritarian, and then to one with layers of control, i.e. a hierarchy. But we are getting ahead of ourselves here. Let’s see whether there is a possible model of the Psychopathic Origins of Civilization.

Let’s suppose an individual within a tribe has psychopathic tendencies. The first instinct, from a civilized point of view is perhaps that he (for it is predominantly men who exhibit such behaviour) will use their influence to rapidly establish power over the tribe. There are two flaws here. First, the concept of “power” in an ancient tribe is a non sequitur – there are no structures to ascend, beyond titular leadership, no ladders to climb, so there would have to be some kind of precedent to first establish the concept of power. Second, such obvious behaviour that could easily be hidden in a civilized society as “mere” ambition would be anathema to the collectivism of the tribe; thus such a person would likely find themselves ostracised or even banished.

So, how could psychopathy work in an uncivilized context? As we have seen, any activity that does not benefit the whole community is not an evolved response to a situation. But, what if certain non-collective activities could be sold to others as being of longer term benefit to the tribe? In other words, could a person driven by personal gain persuade others to do things that could benefit that person alone, in the belief that everyone would gain from these things? This is tricky as there is conflicting evidence as to whether ancient societies had (have) a concept of the future, but there are societies that do exhibit a greater level of forward planning for whatever reason, for instance forest “gardens” and more established settlements. This type of environment would provide a better platform for the psychopath than tribes that predominantly live in the now. So, it may be that a select group of hunters are instructed to stockpile food for themselves, rather than the whole tribe, in the belief that some hunters need to be better fed. In lean periods those select few would be stronger and, as a result of there being less food available, the remaining people weaker.

It doesn’t take a leap of imagination to see the beginnings of a hierarchy here. As this key behavioural change – note, we are still talking about something that is not innate – starts to appeal to a wider group of people who experience short-term personal gain, the simple change in behaviour develops into a cultural change. Acceptance in a small group may bleed down to the tribe as a whole, and thus become embedded in that society; inequalities notwithstanding. The normalisation of having one group benefitting more than others makes more complex hierarchies a possibility, not least because the more advantaged “upper tier” can impose their will upon those lower down. Any tribe that has embraced a culture of power over equality would not be averse to imposing that culture upon others – the belief that whatever is predominant must be morally right is endemic in all modern societies, and thus it is likely to be true in the earliest hierarchical systems. It must, therefore, be “right” to impose its beliefs on all other societies.

Imagine a group of tribes living within reach of one another. If all choose the way of peace, then all may live in peace. But what if all but one choose peace, and that one is ambitious for expansion and conquest? What can happen to the others when confronted by an ambitious and potent neighbor? Perhaps one tribe is attacked and defeated, its people destroyed and its lands seized for the use of the victors. Another is defeated, but this one is not exterminated; rather, it is subjugated and transformed to serve the conqueror. A third seeking to avoid such disaster flees from the area into some inaccessible (and undesirable) place, and its former homeland becomes part of the growing empire of the power-seeking tribe. Let us suppose that others observing these developments decide to defend themselves in order to preserve themselves and their autonomy. But the irony is that successful defense against a power-maximizing aggressor requires a society to become more like the society that threatens it. Power can be stopped only by power, and if the threatening society has discovered ways to magnify its power through innovations in organization or technology (or whatever), the defensive society will have to transform itself into something more like its foe in order to resist the external force.

I didn’t write this essay with the Parable of The Tribes in mind, but it seems I have been led there through logic. Does this make the Psychopathy Hypothesis correct, or could this situation have been reached through other means? Whatever the precise cause, we appear to have a situation where civilization is not inevitable, and instead – shocking to many – the result of a damaging psychological flaw in a very small number of people. This is dramatically different to the myth that the powers that be would have us believe; that civilization is both an inevitable, and a welcome development in human history, and that we should never question the reasons it came about for fear of finding some very unsavoury answers.

A Niggling Doubt

But what if I am wrong? Let’s say we did evolve to become civilized. Maybe the increase in our frontal lobe size, perhaps due to the uptake of cooked meat, created a natural propensity for power and hierarchy, the acquisition of material goods, and the desire to live beyond the beyond the means dictated by our connected selves. Would we be stuck in this terminal situation, or could we evolve again?

In fact this need may be inevitable, for the civilized human is not a natural survivor. Established civilizations thrive where resources are plentiful, including vast numbers of human slaves, and crises for the ruling classes are absent. In the absence of such human and non-human capital, and in the presence of unmanageable crises, civilizations fail…and those who are not adapted to uncivilized living fail with them.

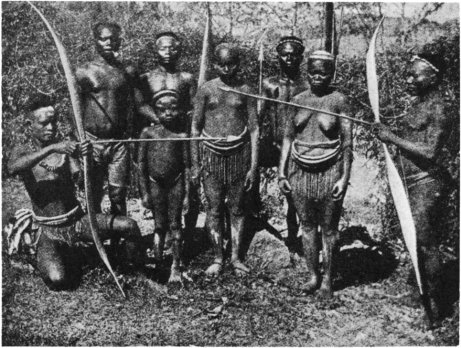

On the other hand, those people who have thus far escaped the hand of civilization have remained connected and more than able to survive in uncivilized conditions. In all likelihood, many people who live within civilization may still be connected, or have the will to become reconnected and relearn the lessons of our ancient past. Those who survive will be the new seed of human evolution. Whether humanity evolved to be civilized or not, the future of humanity appears, in all cases, to be uncivilized.

Note 1: This is the same person who claims that all tribes can benefit from the input of civilization, e.g. Savaging Primitives, by Stephen Corry

Note 2: See, for instance, the extensive work around the concept of Dunbar’s Number – http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/004724849290081J

Civilization is brought about by evolution and the circumstance of significant untouched resource gradients. Mankind evolved very quickly to build expanding tumors by metabolizing these gradients. The soft, molluscan-like humans that have ensconced themselves within technology’s protective shell will soon be expelled back into an environment severely damaged by their own inordinate growth. They will stay within their protective enclosures as long as possible, until the services that make them livable cease functioning or become unaffordable. Then they will crawl across the landscape like great white grubs searching for any still functioning technological habitats in which to shelter. Many will end-up in tents or cardboard boxes or dead after being excluded from the relatively few enclaves where environmental and social conditions remain liveable. Government and businesses and their captive media will silence talk of collapse while filling their pockets with loot necessary to insulate their families from adverse conditions. In an effort to prevent financial collapse, central banks and governments will devise great energy-wasting projects like settlements on Mars, underwater automotive tunnels to nowhere, wars. Just use your imagination, they certainly do. This will finally bring about collapse, the mismatch between exponential financial growth and decreasing availability of energy and other resources. When the jig is up there will be a sudden and massive slaughter of financial assets as everyone tries to obtain some bit of resource gradient that hasn’t already been used up. Then we will likely see war on many levels as many desperate losers try to displace those that have been lucky in the game of musical chairs.

All of the features of human evolution that have resulted in civilization are fascinating, just take a look at a baboon skull, about where we started and compare it to that of a modern human and then imagine what got packed into that cranial space to enable our evolutionary transformation. It all happened very fast, like a cell becoming malignant and growing exponentially.

Pingback: Uprooting Civilization

Interesting post. I’ll come back and read more. I have some ideas about global tribe/civilisation etc to share:

http://olivefarmercrete.blogspot.gr/2016/11/conscious-collective-will-to-good.html

For example….